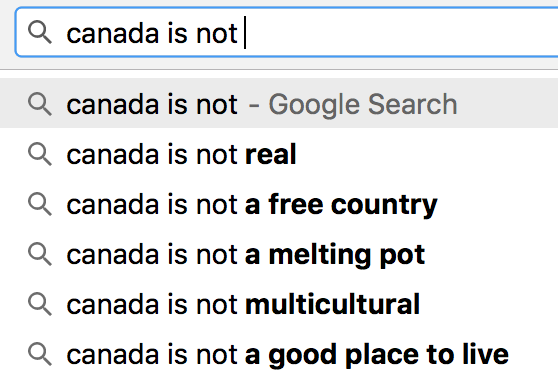

Very shortly after I started this blog I wrote a piece called Canada is not 150 years old which, if nothing else, was a needed addition to the “Canada is not” genre.

My main argument was that 150 years is an arbitrary age to apply to Canada, “too large a number to mark Canada’s independence, too small to hug the full story of a country of nations that is still incubating.” I focused mostly on the incremental stages of colonial history, which include more than 400 years of continuous European-descended settlement, but only 86 years of legislative independence, and only 35 years of constitutional autonomy. Why, I wondered, do we focus so much on Confederation, just one bend in a long river, and let it define Canada’s age so definitively?

I also mentioned the thousands of years of human occupation and cultures that predate European arrival, but I didn’t lean too strongly on that, and I didn’t explain why. Relatedly, when I first announced I was going to spend 2017 blogging weekly about Canadian history, the top response I received was something like “I hope you write a lot about Indigenous history.” Notably, though, those requests all came from non-Indigenous people.

I think there are two main reasons for that. One, you don’t generally hear Indigenous people enthusiastically requesting that settlers tell Indigenous stories, because Indigenous people are perfectly capable of telling their own stories, and because settlers tend not to do a very good job of it. Two, from the perspective of many Indigenous people, their histories and identities are not part of Canada’s, except for the ways in which Canada has harmed them.

Both constructed it as a story about Canada, this is a personal pet peeve of mine. Metis have a history of our own, not a subset of Canada's

— Adam Gaudry (@adamgaudry) January 12, 2017

The nations who were here before the French obviously didn’t think of themselves as Canadian at the time, either. I’ve been writing a bit about the Wendat confederacy for this blog, but by doing so I risk imposing the Canadian narrative and identity on them without their knowledge or consent.

When I published Canada is not 150 years old, a number of people who shared the post agreed with it by way of emphasizing how long Indigenous peoples have lived on this land. Again, all of those people, to my knowledge, were non-Indigenous. The Indigenous people I’m following aren’t generally trying to argue that their thousands of years of histories represent “Canada.” They’re very clear that their histories and national identities stand on their own.

Capitalize Indigenous.

Don't call us Indigenous Canadians.

— âpihtawikosisân (@apihtawikosisan) April 1, 2017

One mercifully unambiguous fact is that today marks 150 years since Confederation, and one clear thing that Confederation did was set off a race of settlement westward, accelerating the pace and intensity of displacement and violence by the new Dominion of Canada against the peoples who already lived here. If you want to insist today is a 150th birthday, then there’s a case to be made you’re talking specifically about the birth of an instrument of colonization.

Canada the country, Canada the confederation, is different from the smaller British colonies that were called Canada before that, and the French colonies that were called Canada before that, and the Indigenous nations that were never called Canada, not in the way we use the word today. In the conclusion to my earlier post about Canada’s age, I wrote:

What’s important, I think, is not that we all agree on the same age, but that we recognize the many shifting boundaries we’ve placed on our story, and what each set of boundaries means. Canada is thousands of years old, and it is a day old, and it has not yet been born.

Today, we’re marking the anniversary of Confederation, the creation of a new legal entity of Canada, one that was determined in many ways to begin anew, painting over a canvass that it imagined, despite all evidence, was blank. Today we’re talking about what that set of boundaries means. Today, Canada is 150 years old.

One thing i have in common with many 39 year old Indigenous people is that we were both born here. So am i still a settler? Do i not belong here, because of where my parents came from? Should people who were here before me get to call the shots, and determine how much right i have to be here?

If so, does that mean i get to call the shots for immigrants, or for people born here who are younger than me, because i was here before they were? This is how some Indigenous people are arguing. If you extrapolate those arguments, they’re untenable, and racist (…if you believe that racism is possible regardless of power/high status. And i do.) You wouldn’t accept me saying that refugees should be *grateful* that i allow them to live here. Likewise, i don’t accept that same attitude from Indigenous extremists.

Someone got on your case for not capitalizing “Indigenous.” i’m here to get on your case for calling me a “settler.” Please don’t. i’m a native-born son of this place, and you can’t send me back to where i came from, because i didn’t come from anywhere else.