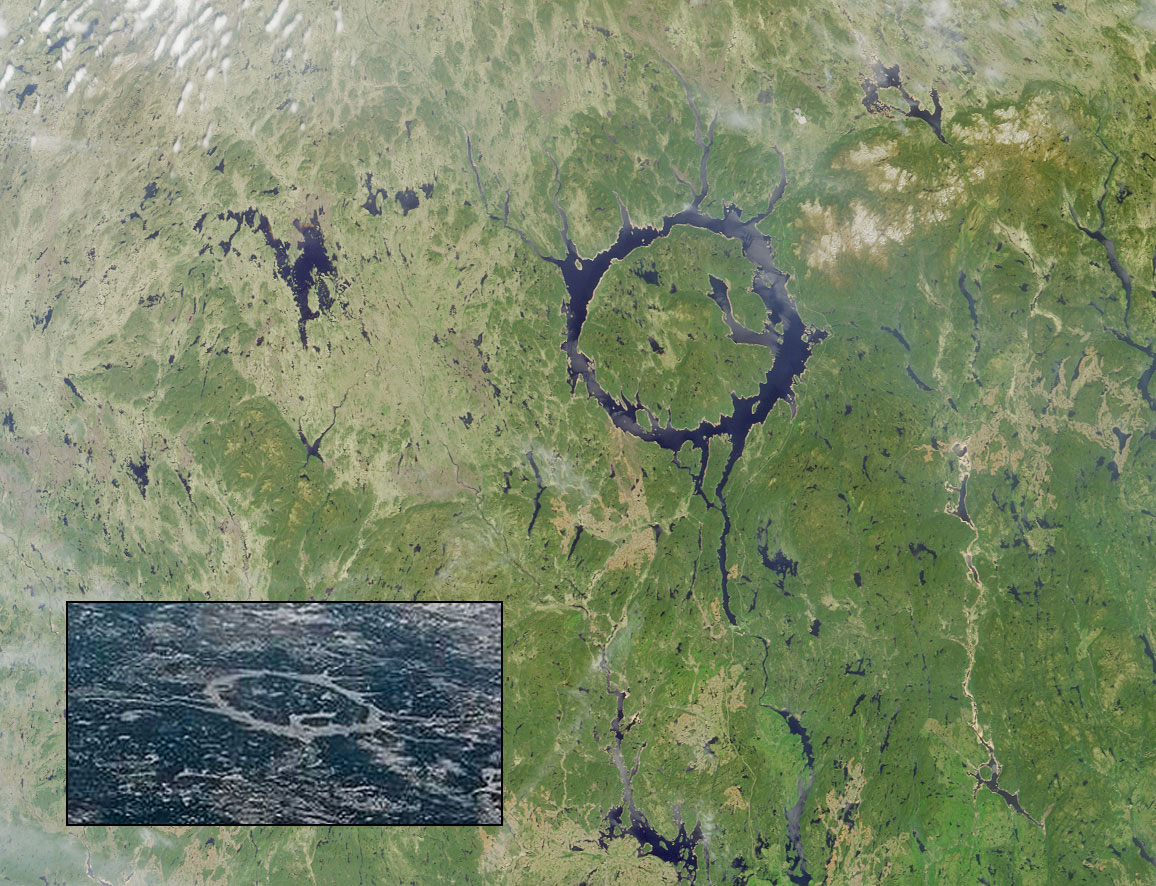

When searching for this website’s header image, I first looked for any photo of Canada from space, because I love space, and because I wanted to try and capture some sense of Canada’s expanse. But when I came across this particular photo, I knew it was the one. Even from space it contains only a small fraction of the country, yet so much has happened in this frame.

At the bottom right, where the mouth of the Saint Lawrence is open widest, we can just barely make out Anticosti Island (l’Île-d’Anticosti). If you want to sail from the Atlantic upriver into Canada, you must first pass this island that David Hackett Fischer calls “the great tongue” of the mouth of the Saint Lawrence. Anticosti was believed to be home to “huge white polar bears” whose “legendary ferocity” was enough to ensure that Europeans and indigenous peoples both gave it “a wide berth.” (Fischer 129)

Further upriver, incredibly visible, we see where the Saguenay River drains into the Saint Lawrence at a place the Innu called Totouskak, meaning “bosom,” and the French called Tadoussac, meaning “we almost pronounced Totouskak correctly.”

This country belonged to the Innu, who the French called Montagnais (the French were always renaming everything), for thousands of years. They camped and hunted in this spot, and were doing so when Jacques Cartier swung by in 1535. When Samuel de Champlain arrived at Tadoussac 68 years later, he happened across thousands of people from “many nations” engaged in a huge celebration. The chance encounter, writes Fischer, was a “moment of high importance in the history of North America” that began an unusually long period of good relations between these indigenous peoples and these Europeans. (We’re sure to come back to this meeting at Tadoussac in a future post.)

Then even further upriver, we can see all the way to Île d’Orléans, and clearly make out that just beyond that island is the point where the river narrows, which is what the Algonquin word Kébec means, which is how the 409-year-old city of Quebec, located at this spot, got its name.

As unlikely as this sounds, we can even see all the way to Montreal and Ottawa. Montreal is identifiable at this distance thanks in part to Lac St-Louis splashing a flash of light at the left edge of the picture just beyond the Island of Montreal, and because the Ottawa River intersects with the Saint Lawrence here as well. We then follow that river up, as if in a canoe, and find the present capital just downriver from where the water takes a sharp turn to the right, before continuing onwards to disappear toward the horizon.

I also like that, beyond New Brunswick in the bottom left, we get a glimpse of the State of Maine, which itself is all mixed up in Canadian history, because the indigenous peoples who lived here for millennia, and the Europeans who fought and traded and colonized here for centuries, did not know they were crossing back and forth over an invisible future line.

Finally, way back on the right hand side, is one of my favourite geographical features in the world: the ring lake Manicouagan, also known as the “eye of Quebec.”

The lake fills the ring of a crater left by an asteroid more than 200 million years ago. “Most craters this age on Earth have long since disappeared,” explains Phil Plait, but this one is preserved by tough Canadian rock.

All that time and all that space, and still so much of Canada isn’t in this photo at all. But I still love it. And only after I began writing this post did I realize the photo was taken by Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield. He tweeted it from the International Space Station in 2013, adding what remains the photo’s official simple caption: “St Lawrence’s mouth, where the Great Lakes pour into the sea.”

fantastic story-telling in this one photo! thanks for this.